Understanding the NZ ETS changes and what they mean for your investment

Recent government announcements regarding New Zealand's Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) have caused market volatility, with carbon prices dropping. However, a closer look at the actual changes reveals a significant market overreaction.

What Actually Changed?

On 4 November 2025, the government announced it will remove the requirement for NZ ETS settings to "accord with" New Zealand's Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement. This change will apply from 2026 onwards[1].

The Paris Agreement is a global climate treaty signed by nearly 200 countries in 2015, committing nations to work together to limit global warming to well below 2°C above preindustrial levels.

In simple terms: previously, when setting ETS rules annually, officials had to ensure they aligned with both New Zealand's domestic targets AND our international Paris Agreement commitments. Now they only need to align with domestic targets. This removes a layer of statutory complexity[1].

An NDC is New Zealand's international climate commitment under the Paris Agreement - our promise about how much we'll reduce emissions.

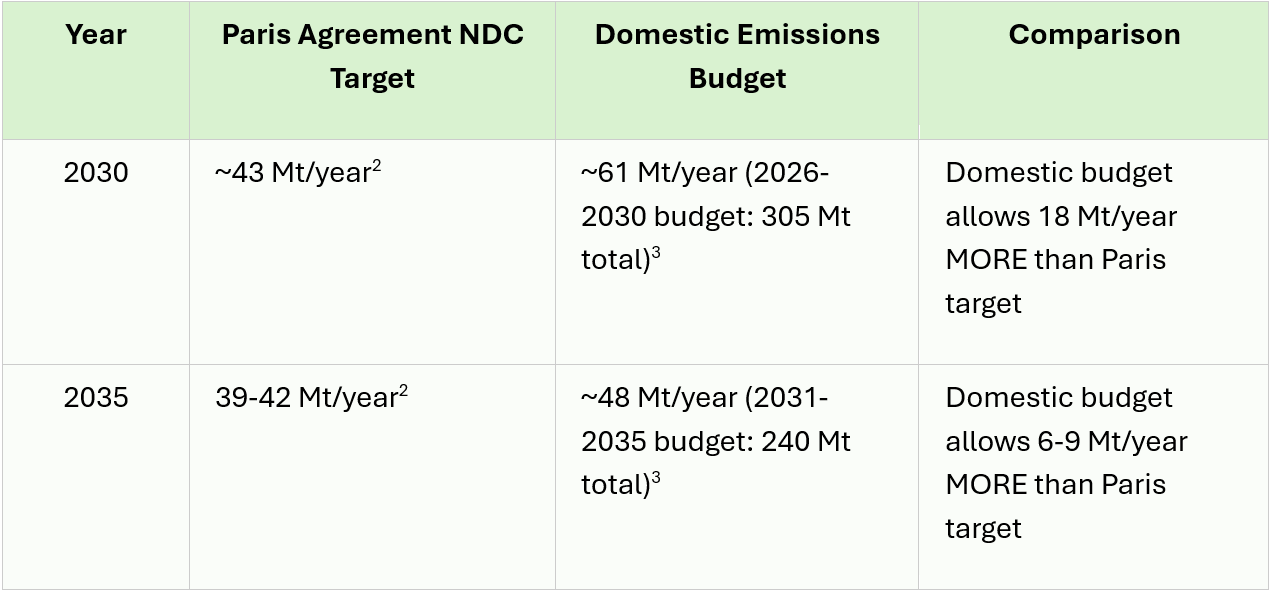

The following table compares the maximum annual emissions levels (measured in megatonnes per year) permitted under each framework. Lower numbers indicate more ambitious targets requiring greater emission reductions from our 2005 baseline of 86.62 Mt CO2-e.2

This comparison reveals an important point: New Zealand's Paris Agreement commitments are actually more ambitious than our domestic emissions budgets. Removing the requirement for ETS settings to "accord with" the more stringent NDC targets doesn't weaken our climate action - the binding domestic budgets remain in law.

Here's what this actually means:

The NZ ETS still remains the government's main tool for reducing emissions and meeting our 2050 net zero target[1]. Net zero means total emissions must be offset by carbon removals, primarily through forestry. New Zealand's actual emissions were 78.4 Mt CO2-e in 20224, requiring substantial emissions reductions alongside significant forestry sequestration.

The requirement for ETS settings to align with domestic emissions budgets and the 2050 target remains unchanged[1]. Domestic emissions budgets are five-year caps that set firm legal limits to keep New Zealand on track. The second budget (2026-2030) caps emissions at 305 megatonnes CO2-equivalent total (~61 Mt/year). The third budget (2031-2035) is set at 240 megatonnes total (~48 Mt/year)[3]. These budgets are legally binding and must be met through domestic action alone. As the table above shows, these domestic budgets are actually less stringent than our Paris Agreement NDC commitments, making the NDC accord requirement somewhat redundant from a policy standpoint.

The structural supply shortfall in carbon units still exists. The Climate Change Commission forecasts the current surplus of approximately 50 million New Zealand Units will be fully drawn down by 2026-2027[5]. All modelling scenarios show the market moving from surplus to shortage within this timeframe, with supply tightness expected from 2027 onwards.

Market fundamentals haven't materially changed - demand remains sticky and supply looks tight over the next few years.

Why Did the Market React?

As one carbon market expert put it: "My feeling is that there was actually very little material market consequence to these changes, and that they are largely in the interests of operational improvements... However, the market reaction was if the regulator suddenly jumped out and said 'Boo!'... because that's a bit how it played out."

The issue wasn't the policy change itself, but how it was communicated. After several government statements that there would be no changes to the ETS, this announcement undermined market confidence.

What This Means for NZL's Forestry Investments

NZL owns approximately $119 million[6] in forestry land (5,488 ha) across the southern North Island, leased to Nateva - New Zealand's largest forestry participant in the ETS and MM Forests Limited. Our forestry investments serve three key purposes:

Generating attractive rental income for shareholders through long-term, inflation-adjusted leases

Contributing to New Zealand's carbon zero by 2050 goal through carbon sequestration

Delivering biodiversity value through our native regeneration programme that combines pine as a "nurse crop" with transition to native forest

The critical advantage of NZL's investment model is that we own the land, not the carbon units or the forestry operations. Our income comes from lease payments, not from carbon price volatility. While our tenants may experience short-term carbon market fluctuations, our rental income remains stable and inflation protected.

The Bigger Picture

The government has reinforced that reducing greenhouse gas emissions is one of nine priority public service targets, and the NZ ETS remains the mechanism to achieve this. The structural need for carbon sequestration hasn't changed, nor has New Zealand's commitment to climate targets.

Richard Milsom

Co-founder and Director, New Zealand Rural Land Management

Published January 2026

[1] https://environment.govt.nz/ chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://environment.govt.nz/assets/Further-Information-Removing-the-requirement-for-NZ-ETS-settings-to-accord-with-New-Zealands-NDC-under-the-Paris-Agreement.pdf

[3] https://gazette.govt.nz/notice/id/2022-go1816

[4] https://environment.govt.nz/assets/publications/GHG-inventory-2024-Snapshot.pdf

[6] As per NZL financial statements, at 31 December 2024